This post first appeared on pygaze.org in July 2015.

TL;DR

One underlying issue in psychopathy is an inability to use contextual information (e.g. the look on someone’s face) to guide attention. New research shows that psychopathic traits are associated with top-down, but not with bottom-up attention. In non-psych lingo: psychopaths are very focussed on the task at hand, and have issues in directing their attention to information that is irrelevant to said task (even if it might have helped them perform better).

(In internet-lingo, TL;DR is an abbreviation of ‘Too Long; Didn’t Read’. Some people don’t like reading long text, and require a super-short summary.)

Attentional Deficits in Psychopathy

In an impressive effort, Sylco Hoppenbrouwers and colleagues tested 30 violent offenders on two or three experiments, in order to assess how attention is affected by psychopathic traits. I was lucky enough to be asked to be involved in the project, to program the experiments and to do some preliminary analyses at an earlier stage. I am a co-author on the publication, but my role was a humble one. The majority of the work was done by Sylco!

After reading the previous paragraph, you might wonder what a violent offender is. The following quote from the paper describes the kind of people that were participants in this study:

Psychopathy

Psychopathy is a personality disorder. It is characterised by inadequate emotional behaviour, which can be divided into two sub-classes. The first is manipulative and deceitful behaviour that lacks empathy (referred to as the core traits), and the second is impulsive and anti-social behaviour. A common tool to diagnose psychopathy is a semi-structured clinical interview (Psychopathy Checklist-revised) that indexes these two factors of psychopathy. People are considered clinically psychopathic when their score on this interview exceeds a certain threshold (true for 10 out of the 30 offenders that participated in our study). For studied offenders, the semi-structured interview produced two numbers: one that informs us up to what extend an individual displays core psychopathic traits (Factor 1, and one that describes the severity of anti-social behaviour (Factor 2).

Attentional Deficits

In earlier work, other people have suggested that attentional problems might contribute to psychopathic behaviour. They conceptualise this as problems of bottom-up and of top-down attention, as well as the interplay between the two. Bottom-up attention refers to things that automatically grasp your attention. Think of a sudden movement in the corner of your eye, or a distressed expression on somebody’s face. Top-down attention refers to what you are prioritising. For example, you could be focussed on green objects, because you are looking for your mounted frog (as you like taxidermy, and you could kill a frog easily). This makes you notice green objects more, and helps you ignore objects with other colours.

Current theories say that individuals with psychopathic traits are so focussed on achieving their goal that they fail to pick up on things happening in their environment. That is: they are less distracted by information that is not relevant to their task. For example, you (as a psychopath) might want to eat a baby’s candy. You’re so focussed on getting the candy, that you miss the look of distress on the faces of the baby and its mother (bottom-up), and you fail to take into account the (distracting!) idea that stealing is illegal (top-down). Of course, this example is a bit simplistic, but the point should be clear: it might be that psychopathy involves rigid behaviour that is not modulated (changed) by signs that it is wrong, because these signs are not attended to. In other words: psychopaths might be so good at focussing on one thing, that they miss all other information.

This definition makes it really hard to tease apart the roles of bottom-up and top-down attention. Are the distressed faces of mother and baby not automatically grasping the (bottom-up) attention of psychopaths? Or are psychopaths so focussed on the candy that they ignore everything else, thus not spending any (top-down) attention on faces at all, because faces are not candy?

Our Study

In our study, we try to provide an answer to this question. We do not use distressed faces to capture attention (as in the example), because these require emotional processing. Psychopaths, by definition, have problems with this. Instead, we use very simple stimuli with specific colours (red or green) and shapes (circles and diamonds). Compared to emotionally loaded stimuli (such as distressed faces), these provide a more pure way of testing attention.

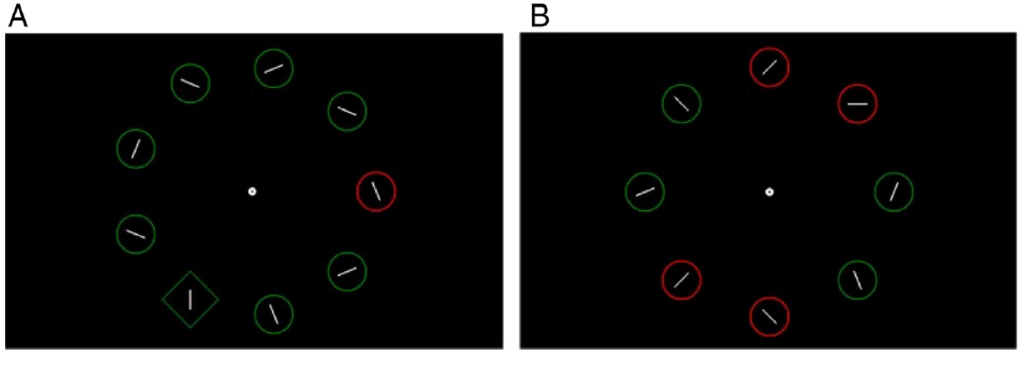

In our first experiment, we tested bottom-up attention. We did so by showing our participants displays with circles and a single diamond, each of which contained a line with a certain orientation (display A in the illustration below). Participants’ objective was to find the diamond, and to report whether the line within that diamond is horizontal or vertical. In half of all displays, the circles and diamond were all of the same colour. Here, participants could simply search for the odd one out. In the other half, one of the circles was coloured differently from the other circles and diamond. This stood out quite a bit, and automatically draws (bottom-up!) attention. Participants were slower to find the diamond, because they were distracted by the circle with the different colour. Crucially, the extend to which our participants displayed core traits of psychopathy (Factor 1) did not correlate at all with how distracted they were by the differently colour circle. Conclusion: bottom-up attention is not affected by psychopathy.

Representation of the attentional capture task (A), and of the visual search task (B). Reference below.

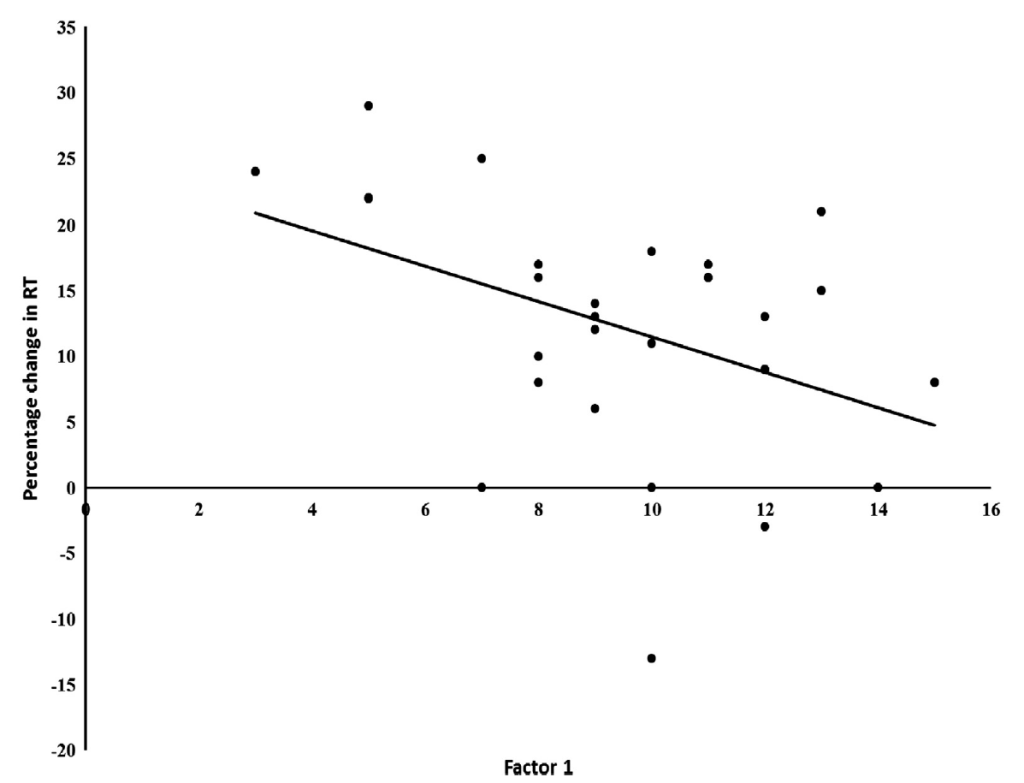

In our second experiment, we showed displays with only circles, each of which again contained a line (display B in the illustration above). Half of the circles were coloured red, and the other half were green. Only one circle contained either a horizontal or a vertical line, and participants had to indicate what the orientation of that line was. So their task was to find the horizontal/vertical line, and tell us what orientation it had. Before each display, we gave participants an instruction. One instruction was simply “attend”. The other instruction was more informative, e.g. “attend green” if the horizontal/vertical line would appear in a green circle. We also used “attend red” if the target line appeared in a red circle, but we never told participants to attend to one colour when the target line appeared in a circle of another colour. Healthy individuals are quicker to respond after the informative instruction, as were most of our participants. However, the more core psychopathic traits (Factor 1) a participant showed, the less able they were to use the instruction to speed up their search! (See the graph below, which was taken from the study.) This suggests core psychopathic traits are associated with problems of top-down attention.

An alternative explanation to the results of our second experiment would be that participants with more core psychopathic traits were simply bored earlier or super-focussed on the target line, and stopped reading the instructions altogether. Therefore, in our third experiment, we made participants rest every 20 displays to make sure that they were not zoning out. In addition, we changed the amount of circles that had the instructed colour. The fewer circles of the instructed colour, the stronger the benefit of the instruction should be: “Attend red” was more informative if only one circle was red (and contained the target line) than when four circles were red (and participants had to search among those four for the target line). The results replicated those of our second experiment: Participants with more core traits of psychopathy were less able to use the instruction to speed up their responses. Conclusion: top-down attention is negatively affected by core psychopathic traits.

Conclusion

Psychopathic traits are not associated with bottom-up attention, thus psychopaths’ attention can be grasped by salient stimuli in their environment. Top-down attention, however, is affected by core psychopathic traits. This indicates psychopaths have trouble with guiding their attention to contextual information that is not in line with their current goal.

In our earlier example this means that when you (as a psychopath) are stealing a baby’s candy, you do process the distressed faces of mother and baby. However, you are unable to use this information to modulate your rigid candy-stealing behaviour, because you fail to process the distress and to associate it with your current actions. (But see the disclaimer below!)

Reference

- Hoppenbrouwers, S.S., Van der Stigchel, S., Slotboom, J., Dalmaijer, E.S., & Theeuwes, J. (2015). Disentangling attentional deficits in psychopathy using visual search: failures in the use of contextual information. Personality and Individual Differences., 86, p. 132-138. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.009

Disclaimer

Some important things to keep in mind: Not all people who display psychopathic traits are clinical psychopaths, and not all people who display psychopathic traits or suffer from clinical psychopathy abide by the principles described above. No single individual is defined by their diagnosis, and taking into account individual differences is important in diagnosis and treatment. The ‘stealing candy from a baby’ example was used because it is simple and engaging, but it obviously doesn’t cover the full depth of the issue. Read the above paper for the complete and nuanced story!